I ran this on my regular blog, Gentleman Unafraid, a few years ago and realized it’s perfect Steppes of Chicago fodder. So, here it is.

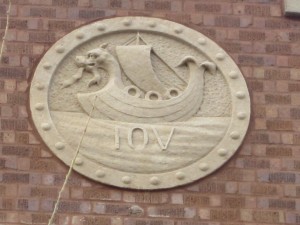

Built in 1909, the Grayland Theater (3940 N. Cicero) was one of several small silent age movie houses in Chicago. Calledneighborhood theaters (according to the fascinating Jazz Age Chicago site), these tiny showplaces skimped on fripperies like balconies, pillars, and ornamentation, and were strictly built to hold a hundred (or fewer) people for an evening at the flicks. When the gloriously decorated, multi-seated movie palaces rose up not so long after, they drained away customers, leaving the neighborhood theaters to wither away. Eventually, most closed their doors. Yet, when compared to the palaces—which have, with the exception of a lucky restored few, been left to crumble or fall before the wrecking ball—an impressive number of neighborhood theaters survived—albeit in slightly mutilated form. Most, in fact, have been remodeled and re-purposed, usually serving as churches or stores.

The Grayland is one semi-survivor. Situated in Irving Park’s Six Corners shopping district, and currently housing Rasenick’s, a work and outdoor wear clothing store, the building doesn’t betray its cinematic past at first glance. Up close, the elements kind of come together. Notice the sedately ornate cornice (a familiar Chicago combo of egg and dart and dentil molding), the former marquee (I’m guessing), and some nice grillwork framing the front window and door. Well, that might not be original, but it still looks pretty cool). The building is, otherwise, in no way outstanding, but it has its Chicago working-class charm. It was built to serve a purpose, not win architectural awards. I came across an account stating that the building was designed by architect William Ohlhaber, who was also responsible for the insane Hermann Weinhardt house in Wicker Park, but that remains to be seen. The theater doesn’t show up on any notable building sites, but while Ohlhaber wasn’t in the league of Sullivan, Burnham, or Wright, he’s still interesting, designing a number of buildings and owning land in West Palm Beach, where he frequently summered.

A few Saturdays ago my friend Pat and I went to watch a Universal monster film festival at the Portage Theater (which, I’m guessing, didn’t help the Grayland’s business back in the day) a block north on Milwaukee. I asked Pat if he’d mind if we stopped by the Grayland. He had no problem with that and mentioned he might even be in the market for some work wear. Entering the store, we walked up an inclined entryway into a large room stuffed with coveralls, safety shoes, and various shades of plaid. As I figured, very little of the original interior remained. A drop ceiling had been installed, and the walls were (if I recollect) wood paneled. A fellow who had worked at the store since 1978 (I think his name was Rich), and who knew a bit about its past, told me the screen was most likely originally located at the front of the store, but the wall had long since been removed. He showed us around a bit, pointing out places where the drop ceiling panels had been removed, revealing a typical, charmingly patterned tin ceiling. I got the name of the store and building owners, so stay tuned for more information. Maybe they’ll let me crawl around a little.

Trolling through the Tribune’s archives, I turned up a few small but juicy chunks of history about the theater. The only record of a film shown at the theater I’ve come across are a series of ads for a whaling film called Down to the Sea in Ships. It starred a young Clara Bow and a little-known silent age honey named Marguerite Courtot. An early blockbuster, Down to the Sea in Ships was heavily promoted not only at the Grayland but also the Rivoli theater on Elston (currently the Muslim Community Center).

What I discovered next, however, is a perfect example of why I love research as much as I love writing. It’s the little surprises; the things that never occur to you; the unexpected tales that pop up during a humdrum review of microfilm or, in this case, online scans. While I’m positive I’m breaking a cardinal rule of journalism by extrapolating from a single article, I’m not sure what else I can do. An afternoon at the library might turn up more information, but I somehow doubt it. The local neighborhood newspaper has only been in business since the 40s, so no luck there either. Maybe I’ll try the store owner and a few local oldsters too, but… Well, heck, let’s get on with the story.

Albert Schmidt was unhappy with his recent purchase.

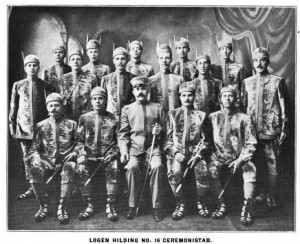

It was October 26, 1926, and he’d just called the previous owner of the Grayland Theater, Samuel Wertheimer, telling him to get over to the place as soon as possible that night. He was having a problem with the ventilation system, and he needed Wertheimer to come over and explain the cockamamie—or whatever expression they used back then—thing to him.

Wertheimer, we must assume, was wary. Schmidt purchased the Grayland only a week before for $4,000. While business was reportedly good—a film was showing when the two men met that day, shortly after 3 p.m.—it wasn’t paying off fast enough. Whether he truly thought he’d recoup the money in that short a timeframe is open to debate, but according to Wertheimer, Schmidt quickly got cold feet and had asked him twice already to back out of the deal. “Nuts to that banana oil, pally! 23 skidoo!” we can only assume Wertheimer said.

It seems Wertheimer cared enough to answer a few questions about the ventilation system’s operation, though. So maybe the bad blood flowed only on one side. Wertheimer showed up in the Grayland’s lobby, then followed Schmidt to the basement. Schmidt indicated the vents, which Wertheimer inspected closely before turning to see… Schmidt standing there with a revolver.

As Wertheimer tells it—and we only have his word for it—Schmidt drew a bead and shot him twice as he tried to run away. Maybe it was dark down there or maybe Schmidt was just a piss-poor shot, but the reluctant theater owner only managed to wing his target, putting a bullet apiece in Wertheimer’s arm and leg. An assumedly distraught, or at the least stressed, Schmidt shot himself, didn’t miss, and died.

Fueled by adrenalin and fear, Wertheimer ran up the stairs, out of the theater, down Cicero Ave. to a local doctor, who bandaged him up while he waited for the cops to arrive.

But that’s not where the story ends.

During the movie, a number of patrons heard the shots, and ran out of the theater (without running into Wertheimer, I suppose). One called the cops. As so often happens during stressful situations, the person making the call got the facts wrong, and instead of reporting a shooting/suicide, this nameless individual reported a riot. Two people had been shot by an unknown assailant, he or she said, and the gunman had barricaded himself in the basement. Seven squads of cops mounted up, armed for rioting bears with guns and “tear bombs,” piled into their cars and headed for Grayland. Some of the cops made it to the theater to discover the cooling corpse of Albert Schmidt.

Others did not.

One of the squads headed west on Addison, sirens howling and lights blazing. Meanwhile, Cecil Chapel, his wife, and and two kids were heading north on Lincoln, probably returning to their northwest side home on Kedvale. Both, according the article, got the yellow light, and both continued driving through the intersection. They collided, adding a bit more blood and broken bodies to the story. Officer Walter Riley, 28, was critically injured and died on his way to the hospital. Meanwhile Chapel and his family, as well as officers Thomas Alcock and George Hennesy were seriously injured. No further details on what became of them, though an accompanying photo made it clear things didn’t look good for Alcock (“AUTO VICTIM. Sergt. Tom Alcock, near death from injuries received in crash”). Ripples expanding outwards from a central pebble of violence cast by Albert Schmidt (listed in his obituary a few days later as having “died suddenly”).

Is anyone else thinking of the opening sequence in Magnolia?

Sadly, the Grayland’s basement was filled in during rehab back in the 50s—at least that’s what the Rasenick person told me. On a more amusing note, the aforementioned 1920s article referred to the theater as being built in “the old style.” Times change.

More info to come, if I come across it.