Why does Chicago hate statues?

Not all of them, of course. The Picasso in Daley Plaza (dedicated August 15, 1967, to hoots and howls of derision) stuck around and endeared itself into becoming a city symbol. Eastwards, the branding scheme that is “The Bean” (aka Clod Bait) is bucking for its job. But many, smaller Chicago idols have been less-blessed, drawing neither tourists nor public sympathy when either defiled, dumped, or disappeared.

Trib writer Donald Yabushi wrote an August 17, 1972 piece about the louts, thieves, and vandals who’d destroyed the Park District’s priceless collection of statuary through the previous century. The article, noting that the PD’s collection totaled about 79 pieces at the time, included a seething quote from Chicago city architect Charles H. Dornbusch:

“It’s a damn shame that these morons and goons can’t find anything better to do than mutilate statues.”

While I completely agree, it should be specified that the morons and goons’ motivations have varied.

Chicago hasn’t always mistreated its statuary. The city experienced a monument boom during the 1890s and 1930s, placing bronzed portrayals of various personages in its parks, on its streets, and elsewhere. Statues tended to be raised through the efforts of four different groups:

- Rich benefactors wanting to give something back to the community (along with their names, usually listed somewhere on the monument);

- Childrens’ groups who saved their pennies;

- Social societies, most often from particular European backgrounds who wanted to display a little ethnic pride; and

- Veteran’s groups, who presented the usual men of war.

With such respectable civic pedigrees, you’d think there’d be greater sympathy toward Chicago’s marble and metal citizens. But, as in any urban environment, if it stands for too long in one place, it’ll be either tagged, damaged, or otherwise vanished by the city’s louts. Yet, the reasoning—if you can call it that—behind such acts differs, running from kicks to politics to profit, and in one case to an act of God.

I’ll just say it: Chicago hates statues. Consider the following as evidence.

*****

The Haymarket Police Memorial is the granddaddy of Chicago statue damage. Certainly, it’s its biggest survivor. Targeted for destruction by the actual forces of anarchy since its 1889 dedication, where other idols have fallen, the bronze cop remains standing like a bronze Rasputin.

The Haymarket Affair remains an open sore in Chicago history, offering a chance to wave the bloody shirt for both left and right, Labor and Capital. On May 4, 1886, 1,000 protesters (mostly workers from the McCormick Harvester plant) gathered in Haymarket Square (on South Desplaines Street, between Lake and Randolph) to demand an eight-hour work day. Someone in the crowd had a different idea, as well as a bomb.

Several speakers addressed the crowd from a wagon set up at the corner, including labor activist and anarchist Samuel Fielden. As he finished the police arrived—180 cops in all, headed by Captain William Ward and Police Inspector “Black Jack” John Bonfield. Ward reportedly held up his hand and said:

“In the name of the people of the state of Illinois, I command peace.”

Though another account claims he declared:

“I command you [Fielden] in the name of the law to desist and you [the crowd] to disperse.”

However, the cap’n might possibly have said:

“In the name of the people of the State of Illinois, quietly and peaceably disperse.”

Who knows? Accounts vary, and anyway his words were soon drowned out.

As Fielden stepped off the wagon, someone threw a dynamite-filled, lead bomb at the police. The bomb exploded, fragging Officer Mathias Degnan with the initial blast, and peppering several others who died later. The cops began shooting. Some reports claim the protesters instigated a gun battle, while others said no, that wasn’t the case. As it stood, Degnan died on the scene, six other cops died of their injuries later, 60 policemen were injured, and an estimated 76 civilians were wounded (Fielden himself took a shot). It’s unclear how many civilians died during the shooting.

The trial quickly followed, and several anarchists (including Fielden)—some present at Haymarket Square, others not—were found guilty of conspiracy and murder. All were sentenced to hang, though two had their sentences commuted to life by Illinois Governor Richard Oglesby. One other, Louis Lingg, literally blew his head off with a blasting cap smuggled into his cell the night before his execution. The four remaining men (Spies, Parsons, Fischer, and Engel) were hanged at the Cook County Jail on November 11, 1887. Frustratingly, the bomber’s identity remains unknown. The entire story of the Haymarket Affair is too large and fractious to be adequately covered here, so I advise a visit to the Chicago Historical Society’s site for greater detail.

Shortly thereafter, it was decided that it was necessary to commemorate the events at Haymarket. Before it even existed, the statue brewed controversy when the Chicago Tribune held a contest to design it. A committee of 25 local businessmen—cleverly called the Committee of Twenty-Five—was established to determine how to best consecrate the shadowed ground. No anarchists or laborers, we may assume, were consulted.

Danish-American artist Johannes Sophus Gelert got the commission. Mr. Gelert is perhaps best-known for sculpting the Herald statue that crowned the now-demolished Herald Building at 165 W. Washington St. (the statue is now located in St. Ignatius College Prep’s architectural fragment garden at 1076 W. Roosevelt Rd.) and the large medallions bearing the heads of Wagner, Haydn, Shakespeare, and Demosthenes hanging in the theater of Adler and Sullivan’s Auditorium Building.

On April 14, 1888, Gelert showed off his model to the 25 in his Art Institute studio. It was scarcely a good gig for Gelert. He had to cover all materials, transportation, casting, and remaining expenses with no more than $4,000 in his budget.

As explained in the article, the statue was designed to feature “a forum, a pedestal and the statue of the officer in full uniform with helmet hat.” Being a product of the reliably conservative Tribune, the article snippily states:

“The forum is so constructed that it can be used as a place for public speaking, therein giving a complete answer to the charge of the Anarchists that free speech is forbidden.”

The irony that the statue’s “right hand is raised to enjoin obedience” was lost on the writer, as was the presence of a billy club at the police officer’s side. “Black Jack” John Bonfield earned his nickname, you see, by keeping the peace with his nightstick—particularly striking strikers..

Not so with the editorialist who wrote a later op-ed piece suggesting the statue established the officer not as the law’s agent, but rather its enforcer—a “monarch” towering over the people he was meant to protect. Feeling saucy, the writer sarcastically asked if the copper-based cop shouldn’t be more of an action figure:

“Shall the action be hitting a head? Shall it be running after a thief? Shall it be handing ladies over a crossing? Shall his sugar scoop helmet be on his head according to regulations?”

More seriously and succinctly, the writer demanded the statue show “that it is law, not the hickory club that is sovereign in Chicago.”

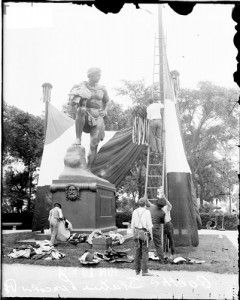

The unveiling took place May 4, 1889, the third anniversary of the riot. A parade of cops, bands, and singers were present. Mr. R. T. Crane of the Committee of Twenty Five presented the statue to Mayor DeWitt Clinton Cregier, while the Hon. Leonard Swett—Abe Lincoln pal, attorney to the Haymarket defendants, and a participant in the commitment of Mary Todd Lincoln to the insane asylum—gave a speech. Chiseled beneath the statue was Captain Ward’s default phrase: “In the name of the people of the state of Illinois, I command peace.”

Anarchists, workers, and citizens injured or otherwise affected by the bombing and shoot-out were perturbed by the highlighting of cops over non-cops, and emotions over the executions of Spies, Parsons, Fischer, and Engel remained raw for the next hundred years.

In seven short years the statue looked shabby. The iron fence surrounding it was “bent and twisted” from constant side-swiping by passing wagons. Public works took half-assed action, placing granite blocks around the base, which interfered even more with traffic (many wondered why the statue was placed, among all possible locations, in the middle of the intersection; the cop’s outstretched hand did nothing to stem traffic). Mud, fruits, vegetables, bricks, and tin cans, spattered and surrounded the pedestal, heaved not by hecklers, but instead escaped from the carts of the costermongers who set up their wagons nearby. The statue was relocated to Union Park, near the elbow of Ogden and Randolph.

Despite the move the bronze cop continued to be brutalized. May 4, 1927, on the 41st anniversary of the riot, a street car carrying 20 passengers hopped the tracks and smashed into the statue. Motorman William Schultz broke his ankle and several passengers were treated for slighter injuries. Luckily, it was the first year since 1886 that the surviving cops (only 23 left by that point) hadn’t assembled to commemorate the event. Local lore claims that Schultz was sick of seeing the Haymarket policemen standing there day in and day out as he trolleyed by, but this seems apocryphal. Per the papers, the trolley’s air brakes failed. The cop was none the worse for wear—and resting comfortably on the ground—but while his pedestal required repair, he was otherwise undamaged and soon restored.

Across the 20th Century, the Haymarket cop was moved thrice, from Haymarket Square to Randolph and Ogden; then to Warren and Ogden in Union Park; then back to Haymarket Square near Randolph and Des Plaines, though 200 feet west of original site. He was also given a brand-new pedestal. On June 2, 1957, the cop was relocated to its original site at the northeast corner of Randolph and Union Streets. Speeches were made, but by this time most of the original participants in the Haymarket Affair were deceased. The last cop standing, Police Captain Frank P. Tyrrell, died 10 years before, but was represented by his son. The rededication couldn’t keep the bronze cop on his new beat though. A year later he was removed to the Randolph Street overpass, commanding peace over the newly built Kennedy Expressway. Later, in 1965, it was designated an historical landmark, but the quiet days (save the occasional tomato or trolley-jostling) were over.

Dynamite exploded between the cop’s legs on October 5, 1969, toppling it from its pedestal, shattering 100 nearby windows, and showering the Kennedy with debris. History repeated itself, and the new Haymarket bomber remained unknown. Unlike the original bombing, however, no one died.

A year later, to the day, the statue was again dynamited from its pedestal, but this time an individual identifying himself as “Mr. Weatherman” called the papers, and claimed credit for the Weather Underground. Mr. Weatherman declared that the statue was blown into two large chunks “to show allegiance to our brothers in the New York prisons and our black brothers everywhere.” Days later, another story emerged when an unidentified woman wrote to the Chicago Free Press, claiming she’d participated in the bombing, intending it to be a signal for further explosions. “Blowing up the pig statue was easy,” she said, stating that months before a Weatherman cut his hair and took a job in southern Illinois as a construction company watchman to pilfer the required dynamite.

Original recipe Mayor Richard Daley was livid, and ordered 24/7 police protection for the cop. This prompted a peculiar letter to the Trib from one “S.J. Mirecki.” Mirecki calculated that the round-the-clock guardianship of the Haymarket cop was running about 50 grand a year (the Tribune says it was $68 grand), and suggested instead that the natural bronze police be covered by a plastic bubble, “television replay cameras,” and “bulletproof floodlights” (Mr./Ms. Mirecki apparently didn’t calculate what such hi-tech surveillance/containment might run). The idea went unheard, and the statue was once again moved elsewhere.

Deciding the best defense was a building of cops, the peace-commanding officer received a transfer to Police HQ. After a thorough cleaning, it was briefly stored before the move. But he wasn’t done moving yet. Four years later, the Haymarket cop went undercover after being moved to the Chicago Police Academy’s courtyard (1300 W. Jackson), away from public view.

In 2007, the statue was re-rededicated at its current location, the newish police headquarters building at 3510 S. Michigan. The statue is once more on public display, in that you can see it if you stand on the 35th Street sidewalk. I wasn’t feeling courageous enough to ask the nice officer in the booth if I could approach the statue. The “Police Access Only” sign on the parking lot gate seemed to answer my question.

By the way, the police-commemorating Haymarket Monument isn’t the sole memorial to the tragedy. A semi-abstract, labor-friendlier monument bearing faceless Playmobil-like figures propped around and atop a wagon has stood at the original site since 2004. And way back in 1893, a monument to the anarchists was set up in Forest Park’s German Waldheim Cemetery. Standing above Lingg, Spies, Fischer, Engel, and Parsons’ graves is an heroic Albert Weinert statue of Lady Justice—laying a laurel on a dead worker’s head while drawing her sword.

General John A. Logan’s monument in Grant Park has seen considerably less abuse, though it may be more recognizable to outsiders. The general was a Civil War hero and politician, and was instrumental in the creation of Memorial Day. His monument, however, is best known for being infested by yippies during the 1968 Democratic Convention. When not being crawled upon by young revolutionaries, however, the General regularly had his sword snapped off by souvenir-seeking idiots. By 1972 the General had been symbolically castrated no less than four times, each sword costing 400 bucks (1970s money) to replace.

While most statue damage can be attributed to kicks-seeking idiots, some statue defilers apparently consider themselves art and social critics. The Weathermen editorialized with dynamite, but some vandals prefer mixed media. Naturally, taggers and other graffiti-scribbling doofuses have always been with us (a photo from Yabushi’s article shows the base of Lincoln Park’s Lincoln monument scrawled with the peculiar graffito “MICKEY MOUSE”), but their defilement, motivated by brainless self-promotion, is rarely directed at the work itself. Art-hating vandals, however, have presented their criticisms via color-coded commentary.

The Goethe statue, in Lincoln Park took its share of anti-Germanic sentiment during WWI. The fact that German immigrants loyal to the US had helped build (and rebuild) Chicago in the previous century, and dedicated other, less-attacked monuments across the city (including ones for Beethoven, Schiller, Alexander Von Humboldt, and others, was irrelevant. Sculpted by Herman Hahn and dedicated in 1913, the not-the-least-bit-homoerotic statue can be found saucily thrusting out his hip and derriere while proudly showing off his pet eagle at N. Sheridan Rd. and W. Diversey Pkwy. The statue doesn’t depict Goethe himself—in his later years he somewhat resembled Geoffrey Rush—but instead represents his art, ideals, and status as (per the inscription) “The Master Mind of the German People.”

On the evening of May 7, 1918, two bravely anonymous individuals splattered the statue with yellow paint. Individuals unpossessed of climbing or hurling ability, it appeared, since the statue was only yellow from the knees down. They left a note explaining their art action and revealing the country had a more literate brand of jingo back then.

“An empathic protest from a free people against the retention of what has always been an offense against art, and now is a challenge to loyalty. Shall this park, named for the illustrious Lincoln, continue to harbor such an enormity or will the people of Chicago insist on its immediate removal? [signed] TWO AMERICANS”

Very likely the statue’s massiveness and the comparatively small stature of the two Americans led to nothing more than spattered shins and a sticky paint puddle near the statue’s base. The US flag’s colors may not run, but the anonymous paint-vandals and their pigment did.

Per the papers of the day, other anonymous threats were made to toss the “enormity” into Lake Michigan. Such individuals were likely unaware that the statue weighs several tons. Admittedly, witnessing an angry mob hoisting and toting it lakeside would have been something to see.

The Goethe statue’s fiercest critic was Mother Nature. On the rainy morning of September 14, 1951, local residents were shaken awake by an enormous thunderclap. After the storm the Goethe and its base were found ridden with cracks and “twisted.” The nastiest spot of damage, however, was its left foot, now splayed wide open. In all likelihood, the statue was smote with a lightning bolt, which exited through its body and out the furthest limb.

The police cordoned off the area, and the Goethe statue was left to stand on its sore foot for two years before being removed for repairs. Chicago sculptor Fred Torrey cast a new bronze foot from the original model. Torrey’s other local work includes the bas-reliefs adorning 333 N. Michigan Avenue, and the memorial plaque of the capture of the U-505 Submarine at the Museum of Science and Industry. By July 14, 1954, the Goethe was reshod, cleaned, polished, and set aright on its pedestal.

Decades later, Joan Miró’s sculpture Chicago (originally titled The Sun, the Moon, and One Star) had been nestled between the Cook County Administration Building and the Chicago Temple—stuck in an eternal face-off with the Picasso across the way—for a few bare days. Then on May 1, 1981, art student Crister Nyholm beheld it, frowned, and returned home to pour red paint into an orange juice container. Returning to the Miró, he hurled paint at it, then sat down and waited for the police, telling the officer he did it because…he didn’t like the statue. In a later TV interview, Nyholm presented a better, if more bizarre, art statement, claiming that 20th Century art “disgusted” him, and the statue reminded him of a “dead body,” Conservators from the Art Insititute used a “paraffin-based solvent” to strip the paint without harming the monument’s porous concrete. Meanwhile, the judge sentenced Nyholm to 30 months felony probation, the cleaning bill ($17,037.21), and perhaps anonymity, since I have yet to turn up anything else about his post-Miró molestation life.

And the paint keeps flying. Last year the dreadfully irrelevant and thankfully now-absent statue of Marilyn Monroe that stood in Pioneer Court was splashed up to her bloomers with red paint (just a month after having her legs tagged). It seemed to be the capper after months of complaints by local art critics and aficionados, and a parade of unimaginative tourists snapping shots of themselves looking up her skirt.

For rampant statue carnage, nothing beats the forgotten American Bronze Works fire of 1901. Located at 73rd and Woodlawn, the plant cast historical figures and other monuments for Chicago’s parks and elsewhere. Previous examples of their artistry include the Haymarket Square cop and the Art Institute Lions. On the morning of February 10, a fire broke out, doing $5,000 in damage and melting and scorching several statues in progress. A sketch accompanying the article shows the resulting rubble, with girders and machinery sticking out of piles of bricks, interspersed with busts, swords, and the odd horse leg. Fallen idols included a group of “Battle Creek soldiers,” and a bronze statue of Speaker of the Indianan House of Representatives William H. English. But, seriously, the hell with that guy and his statue. Look upon his works and despair.

*****

Vandalism is, of course, costly, offensive, and unsightly, but there is the tiny blessing of having a statue to repair. Not so with several statues that vanished some dark evening. The crime was usually covered up for days (or more) by the invisibility of familiarity, until someone stopped, looked, and said, “Something’s missing here.”

Historically, statue-erecting takes place during periods of prosperity, when discretionary income can satisfy the urge to immortalize (it’s surprising how many children’s groups could afford to pay for statues, stained glass widows, and similar fripperies throughout the 1880s and 1920s). Likewise, statue theft occurs during leaner years. Motivated by metallurgy rather than aesthetics, the thieves topple idols and cart them off for scrap. Statues costing thousands of dollars ended up melted down for a pocketful of bills. For example, up in Lincolnwood last January, the scrap collectors showed they don’t care a fig about dead autistic children, so long as they could clear a few bucks in the sale of the bronze—which the statue wasn’t made of anyway.

Not many people know a bust of Beethoven once occupied a spot in Lincoln Park’s Grandmother’s Garden near (Stockton and Webster), not far from the Schiller statue’s gaze. Schiller remains, but Ludwig is long gone. The bust, another work by Johannes Gelert, was dedicated on June 19, 1897, and donated by Chicago concert pianist and early, ardent CSO supporter Carl Wolfsohn—lover of lovely, lovely Ludwig Van. Asked to say a few words, Wolfsohn trumpeted the the deaf composer’s legacy:

“…when the hundreds and thousands that seek rest and recreation in our park pass this beautiful spot, standing before this monument, ask who is this, let the answer be given: ‘Ludwig Von Beethoven, the greatest musician and greatest benefactor of mankind.'”

Perhaps many did—the bust sat there for 74 years—though no media mention is made about it until 65 years passed when complaints were lodged about the bust’s increasingly shabby appearance. Park District officials investigated and declared that Beethoven was supposed to look greenish, because that’s what bronze does outdoors. However, vandals had slathered the composer’s face with a “black substance.” Easily fixed, the offending ink/paint was buffed away without disturbing the aforementioned patina. Eight more years passed before the bust was heard from, or rather not heard from, again.

Sometime before April 26, 1971, some rube with a truck pulled down the composer of the “Moonlight Sonata” and Ninth Symphony, and likely toted him off to be sold for scrap. Police found no clues other than the abandoned rope. A part of the base remains in Grandmother’s Garden, easily overlooked by passersby.

The original inspiration for this article came from a reference in the WPA Guide to Illinois, created by the Federal Writers’ Project. One itinerary advised that tourists visit the Emanuel Swedenborg bust on Simmons Island. Never having heard of either monument or island (though I was partially familiar with Swedenborg the man), I looked up both, only to discover that while the island remained, the bust did not.

Emanuel Swedenborg is an intriguing figure; certainly one unexpected to show up in bronze form in Chicago. The man was a scientist turned theologian/Christian mystic, and his religious notions (achieved through visions) served as the seeds for a branch of Christianity appropriately named Swedenborgianism. As a scientist, he was a true man of the Enlightenment, studying mathematics, metallurgy, chemistry, anatomy and physiology, and other disciplines. As an example of what his big 18th Century brain was capable of, he developed interesting theories about the operation of the nervous system and pituitary gland.

As a mystic, well… the man claimed to talk to angels and pay visits to heaven, hell, and all the planets (yet-to-be-discovered Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto were somehow omitted) to speak with the spirits living there. The man’s legend is also borne anecdotally by stories of supposed psychic talents: predicting fires, reading minds, and whatnot. Don’t be hasty to judge: Swedenborg may or may not have been nuttier than a granola bar, but he wasn’t a bad guy. He preached (strictly through his writings; he had a speech impediment and never started a church himself) the usual messages of peace, love, understanding, and a theory of “usefulness,” and he inspired people like Ralph Waldo Emerson and city planner/architect Daniel Burnham (who was a Swedenborgian), Back then and today, he has his share of admirers and supporters.

Mr. and Mrs. L. Bracken Bishop donated the bust, finding it in Upsala, Sweden, and paying a grand to cast it in bronze. The Bishops considered giving it to the city of Washington, DC, but Mrs. Bishop preferred Chicago and its sizable Swedish population (more on Chicago Scandinavians can be found here). Sculpted by Swedish artist Adolph Jonsson, an early press kit notes he was a stickler for details, employing “studies of Swedenborg’s skull” to achieve the perfect likeness. Incidentally, while rich folk money bought the bust, the pedestal was purchased with pennies, nickels, and dimes donated by hordes of Swedish kidlings.

The statue was unveiled and dedicated on June 28, 1924, with several thousand Swedes, Chicagoans, and Swedish-Chicagoans in attendance. A “white-capped” chorus of 1,200 Swedish singers (coincidentally, in town for convention) and a Viking ship float crewed by ladies dressed as Valkyries sang that stirring old Viking battle hymn, “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” Mayor William Dever accepted the bust on behalf of the city; a congratulatory letter from President Calvin Coolidge was read; and for extra Svenska goodness, Swedish Minister to the US Axel Wallenberg gave a speech. To Chicago’s Swedes, the bust was a big deal—though Swedenborg wasn’t alone. Other Scandinavians immortalized in bronze around town include Leif Ericson in Humboldt Park, and, as a neighbor to Emanuel, the botanist/zoologist Carl Linnaeus. Linnaeus’ statue, before being moved to its current Hyde Park location, had its own problems, when, in 1972, its arms were snapped off. Coolidge’s letter and other encomiums praised Swedenborg the scientist but skirted Swedenborg the astronaut ghost whisperer, save for professor C. G. Wallenius, who described his predecessor as first “a great investigator and scientist,” and later “the picture of a supernatural prophet and seer.”

Swedenborg’s bust remained on Simmons Island for the next 52 years, quietly mulling the secrets of the universe and making mental day trips to Alpha Centauri. Easily overlooked, thousands of people drove past it on Lake Shore Drive for years, either never taking notice or wondering what Benjamin Franklin was doing there.

And one unknown day, in January/February of 1976, it vanished—just like that. Made of bronze and weighing several hundred pounds, the only logical explanation for its disappearance was that it ascended into the heavens…or perhaps some goon and his jackass buddy pulled it down and loaded it into their van. The metallurgist’s bust fell victim to scrap collectors. The cops put the value of the metal at around 10 grand, which seems a bit high, though the country was experiencing a recession. For the next 34 years, Swedenborg’s bust was replaced by a squat pyramid, and in 2009 the pedestal was struck by a car and badly damaged, though later repaired. Finally, in 2010, a new bust was recast and the site was rededicated to the erstwhile religious rocketeer. Godspeed you to Venus, Commander Swedenborg.

In another utterly tacky case of statue abduction, on October 1, 1941, Chicago Postmaster Ernest Kruetgen reported that the bronze statue decorating his family mausoleum at Graceland Cemetery was missing (conveniently, here’s a picture of it on eBay). Kruetgen imported the statue from Germany in 1918; weighing in excess of 750 pounds, it cost the former postmaster about $1,500. It stood at the mausoleum’s door for decades, until Mssrs. Alexander Stazhurski and Theodore Brzozowski drove into Graceland one morning and threw it into their car. Yes, in the morning. Statue snatchers are rarely criminal masterminds, getting away with it mostly by plying their trade at night and finding places to cash in that won’t lead the cops to their door.

But Alexander and Theodore were neither careful nor connoisseurs. Plainly, they hadn’t thought things through. No scrap or junk dealer would touch an obviously hot statue. Not one that was intact anyway. So the Philistines armed themselves with hammers and went to work on it, shattering it into unrecognizable chunks and paying some ragamuffin a dollar to sell it at a North Avenue junkyard. For all their work, they netted just $31.50. Or rather $30.50 after they paid aforementioned ragamuffin. But the chunks weren’t unrecognizable enough, and the dealer called the cops. Once nicked, Stazhurski and Brzozowski confessed to everything. Kruetgen, as a recent visit to Graceland showed, never bothered to replace the statue. Its base remains bare.

Like Kruetgen’s grave babe, some statuary is more stolen than others. An original Paul Gauguin statuette titled “Woman with Parasol” was snatched from the Main Street Bookstore formerly at 742 N. Michigan. The nine inch knickknack had a sale price of $1,500, and apparently was never recovered. Across town, on October 17, 1957, catering hall owner Mario Conti had five statues stolen from him during his new hall’s construction (located at 5609 North Ave., the building was the former Ferrara Manor Theater. The lot is currently occupied by a Walgreens). The purloined statues were itemized as four “females” and a fountain topped by Roman ocean god Neptune. Newly arrived from Italy, the statues were five feet tall, 250 pounds each, and coincidentally priced at $1,500 apiece. The account is sparse, and the record remains silent on their eventual fate, making me envision a yet-to-be-discovered secret apartment or home decorated in a Neptunian theme.

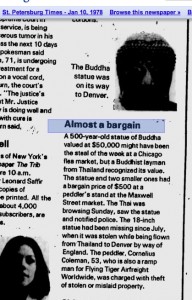

Luckily, not all statues stolen in Chicago are destined for oblivion. On January 8, 1978, a Thai Buddhist church official (no name available) spent his Sunday at the old Maxwell Street Market. Amid the blues and bric-a-brac were several Buddhas—one large and two small—sitting amidst peddler Cornelius Coleman’s wares. The Thai gentleman recognized the statues’ exquisite antiquity—500 years old and valued at $50,000—and status as contraband, having been stolen en route from Thailand to Denver months earlier. The official informed the police. As it turned out, Mr. Coleman worked as a ramp man for Flying Tigers Airfreight Worldwide. Coleman was charged with theft of stolen or mislaid property. He’d priced the statues at $500. A true steal.

Nothing was sacred for Old St. Patrick’s Church either. On December 26, 1970, 18 of the statues in its 40-year-old creche were snatched. The Trib listed the abducted: three wise men, three shepherds, one camel, one lamb, and Mary, Joseph, and Lil’ Baby Jesus. I’m not sure about the frequency of crèche theft (holy cradle robbing?) before 1970, but the story seemed uncommon enough to report on. Mr. Willie Brown, 31, was arrested, the police’s suspicions raised as he sauntered down Adams Street with a holy parent under each arm. The rest were discovered later on by local printer Roy Hobby, stuffed in a pile of crates in a parking lot near Lou Mitchell’s.

Daniel Chester French is probably the most recognizable sculptor in this essay—by reputation if not name. Roundabout March 15, 1986, French and his student Edward Potter’s “Bulls World’s Fair Models”—a pair of, yes, bulls, attended by two maidens: togaed Ceres, Roman goddess of commerce and grain, and a “Native American goddess of corn”—stood guard in Garfield Park since 1909, before thieves filched the bull and his Native American lady friend.

As a matter of trivia, French made the goddesses while Potter sculpted the bulls. French is best known for his statue of Abraham Lincoln—the great big one in Washington, DC—the Concord, MA Minute Man statue; and the Pulitzer Prize Medal. Potter, by the way, made the lions standing guard outside the New York Public Library. The Indian maid and her bull weren’t masterpieces, but they were remnants of the Columbian Exposition, and thus precious to a city enamored of its first moment in the world’s spotlight. Originally, the statues were plaster, and stood at the World Fair’s livestock exhibit. Afterward they were transported to Garfield Park, where they proved popular, were eventually cast in bronze, and placed outside the Conservatory.

Bolted to two-foot-high granite slabs and weighing at least a ton, the bull and maiden couldn’t have been easy to steal. A crane and truck were probably used, and according to a September 12, 2010 article by Mary Schmich, rumor was it was an inside job—though there’s no way to prove it. The thieves attempted to take Ceres and her bovine pal as well it seems, since the Roman god-maiden was missing an arm and the bull its tail. The case of the bulls suggests the thieves were men of taste, rather than just greed, anarchy, or excessive doobage. Though one wonders why the arm and tail of the other pair were snatched as well. Perhaps the initial intent was to sell the statues for scrap, but the dealer had a good eye and the right connections to find a nice rich person to sell it to. The CPD posted an award for $1,000, but no one claimed it, and the statue was designated missing/assumed melted. In 2003, the CPD hired art restorer Andrzej Dajnowski to repair Ceres and her bull and to replicate the other statue, which is currently on display. Previously, Dajnowski restored Lorado Taft’s Fountain of Time in Hyde Park

Then in February 2010, Chicago Park District historian Julia Bachrach received an e-mail from a New York auction house. They’d come across a certain statue, found on the estate of a recently deceased Virginian. Were they missing any bulls or maidens? Little more information was revealed as to the statue’s provenance (the Virginian’s name was suppressed, per a legal agreement with his family, though they said he was only the third owner). Plans are afoot to restore the original bull and Indian maiden, though they are currently in storage.

In a June 18, 1976 article, Trib writer Paul Gapp interviewed Friends of the Parks president and former Chicago Park District commissioner Cindy Mitchell about the abuse and neglect of our town’s statues. The piece makes intriguing mention of several long-missing figures that seemingly went poof, temporarily or permanently. Such as the massive 20-foot, 14-ton statue of Christopher Columbus, set up in Grant park in the 1890s (the current Columbus statue in Grant Park went up in 1933). Accounts state that the previous Columbus was removed owing to the prevalence of “loiterers” in the area—use your imagination as to why they were loitering, I guess—and stored away. Mitchell learned that in 1903 it was melted down and remade into a monument to America’s third assassinated president William McKinley—now standing in McKinley Park at 38th and Western. Ms. Mitchell also found out that Chicago was down two Minutemen—one in Lincoln Park and one in Garfield Park—and a sylphic young miss named Fountain Girl (aka, The Little Cold Fountain Girl).

Another idol built with urchin allowances ($3,000 paid to sculptor George Wade in 1893), Fountain Girl was the brain child of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). The ladies wanted to provide an alternative to hootch on the street. Originally stationed near the WCTU’s booth at the Columbian Exposition, FG was later moved to LaSalle and Monroe, near the Women’s Temple (built by Burnham and Root in 1891-92; demolished in 1926; look closely at the postcards here—I think you can just make out the statue at right). She ended up in Lincoln Park near Lake Shore Drive and North Avenue, until LSD construction led to her being put in storage. In the 1940s she was placed near the W. LaSalle Dr. underpass before being snatched sometime in the 1950s. But 21st Century enemies of Demon Rum can take heart. Turns out there were at least three copies made of the statue, placed in the cities of London, Detroit, and Portland, ME. According to the parks site, a new casting is being made of Portland’s Fountain Girl, and she may well end up back on her empty stone perch before long.

The missing Fountain Girl and bull-maidens raise one other interesting point. Chicago has few to no statues of actual women. In Ver Meulen’s aforementioned article, there is brief mention of one of Chicago’s very few statues of an historical woman (that is, a real woman, rather than an abstract concept like the Picasso (possibly inspired by artist’s model Sylvette David/Lydia Corbett) or a mythological babe like the creepily faceless statue of Ceres atop the Chicago Board of Trade). Once upon a time, a Joan of Arc bust rested at 5801 N. Natoma Ave. in Norwood Park. Eventually it didn’t. It remains unknown if it was lost, stolen, or stored away and forgotten. One hopes it wasn’t subjected to the smelter’s scorching heat. Considering its namesake’s fate, that would be entirely too weird.

*****

Why does Chicago hate statues? Perhaps it doesn’t, as shown by current efforts to replace many of the busts, monuments, and other idols lost and fallen over the years. But the true proof rests in whether the city’s citizens are willing to make a greater effort to appreciate its statuary.

Consider visiting some of the overlooked monuments in your neighborhood and elsewhere. Enjoy the history and grandeur of these idealized metal men and women. Concentrate on the details: from the iguana resting at William Humboldt’s feet (Humboldt Park); to the box of cigars resting behind Sam Gompers (Gompers Park); to the impressive bronzed boobs on Joseph Rosenberg’s fountain for thirsty newsboys (Grant Park). Ponder how General Logan might have avoided hippie infestation by being located in Logan Square, and wonder why General Grant guards Lincoln Park instead. Above all, take notice of them today, because the evidence bears out they might not be there—in whole, in part, or even unmarked—tomorrow.

—Dan Kelly