Fraternal Orders

The nice people at the Latvian Folk Art Museum and Latvian Community Center—discussed in this previous entry about the former Independent Order of Vikings Ivar Temple—shared the following picture of a “Viking” drinking horn with a decorative dragon they discovered in the basement. The Latvian Museum folks graciously donated this and several other rediscovered IOV items to Chicago’s Swedish American Museum. Sounds like a good place for a future visit.

I’m omitting the last names of several of this entry’s dramatis personae because the subject matter is rather sensitive. The Steppes of Chicago blog has been a great success in that we’ve received many interesting comments from folks who either live or lived in the neighborhoods we cover. Long-time Chicagoans tend to be entrenched (my own family’s lived in the region for over a century), and it’s likely the boy mentioned in this piece still has relatives in the area. Nothing can really be gained by putting his family name back in the public eye after 66 years, I think. At least in this instance. Agree? Disagree? Comment away!

If Frank T_________, age 13, was looking for a little attention, 1946 gave him more than he expected. Living with his mom and three younger sisters at 3838 Grand Ave. (still standing, though the former ground-floor tavern is now a Vienna Beef hot dog joint), Frank knew tragedy early on. The previous year his father Anthony was killed at 4207 North Ave. Mistaking the apartment for his sister-in-law’s place, Anthony was shotgunned by Mr. Edgar B_____ and died the exceedingly young age of 34. Left to raise four kids, Lillian T________, 33, presumably did the best she could. However, a subsequent series of Tribune articles from that year reveal that young Frank wasn’t always operating under adult supervision.

His first appearance is a lark, or at least a schoolboy prank (interestingly, he was a schoolboy at Our Lady of the Angels School, though many years before the fire). On March 15, 1946, Frank and his buddies decided to break in and skulk around the abandoned New Apollo Theater at 1536 N. Pulaski. One can completely understand why the place would be irresistible to adventurously stupid young boys. Built in 1913, it closed after 20 years and was left to rot. One reporter’s account describes a cavernous, ramshackle deathtrap, complete with collapsing walls, drooping floors, trapdoors, and copious cobwebs straight out of a Universal monster flick. What preteen lad with more curiosity than brains wouldn’t want to explore it?

Eight years before Frank and his friends showed up, Dewey B_______, 14—who lived next door—and Donald J______, also 14, tried to enter the place on August 17. Accessing the roof—perhaps from Dewey’s building—they chose a ventilator shaft as their point of entry. Undoubtedly surprised when the shaft door beneath them collapsed, they soared straight down. God loved fools and children even then, because Dewey and Donald (Huey and Louie were likely elsewhere) fell only 15 to 20 feet to the rafters, rather than farther down to the theater floor. Donald broke a leg, while Dewey broke his right arm, making him the obvious choice to crawl out and seek assistance. Finding his way out, he called for help, and firemen arrived to rescue the two early urban explorers from the theater and themselves.

That the theater remained standing until Frank’s prepubescence is remarkable. At a guess, the place acquired a taboo cachet ever since Dewey and Donald’s misadventure. Likely, many others entered the place before and after, but Frank’s is the only trip (besides the other boys’) that’s on the record.

As Frank and his buddies walked the aisles, a local flatfoot grew wise, entered, and ordered them out. His friends scattered, and our young hero ducked under a stage trapdoor, closed it, and discovered a tunnel about 3 1/2 by 3 1/2 foot high. As with many a boy before him, “tunnel” equaled “adventure,” and Frank crawled on, apparently not bothered by the ickiness and vermin one would expect in the innermost recesses of an abandoned movie house. Apropos to the occasion, the tunnel, Frank reported, ended in a four foot by four foot room littered with business cards, crumpled rags, a derby with a hole through it, and your standard human skeleton.

With only two short articles covering the story, the sequence of events grows murky, so bear with me.

When he saw the bones, Frank claimed he yelled in terror and crawled back out. I picture him yammering like Lou Costello about the sk-sk-sk-skeleton down there to the cop who told him to scram.

Later on, he gathered his courage in the presence of the cops and reporters and went back into the tunnel, emerging with the battered hat and stack of cards. A photograph accompanying the Trib story shows him holding A hat, sticking his index finger through A hole, but you have to wonder why the cops were letting him handle potential evidence. Perhaps a photographer or reporter found an old chapeau and said, “Hey, kid. Hold this for minute, willya?” Certainly not.

The stack of cards was interesting. It contained two fraternal order membership cards (which organization wasn’t specified) for Messrs. Karl H. Weis and H. Austenmueller, and numerous “theater cards”—presumably advertisements for various shows. The cards came from the days that were considered the “good old days” even in 1946. The cops traced them to Mr. Weis, who ran a bakery at 1744 W. 35th St. Weis remembered having the cards, said he had Mr. Austenmueller’s card after paying his membership fee, and further stated he’d lost the cards while changing a tire on Elston Avenue back in 1919. As to how they ended up under the New Apollo Theater, he had no idea. A likely story.

This is a 1902 photo from the Oriental Institute at U of C. But you get the idea.Cite as: DN-0000217, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum.

Actually, it was an irrelevant story. There was still the little matter of retrieving the skeleton. When the cops went to recover it, they found two feet of water in the tunnel Frank failed to mention. The fire department planned to pump it out, but now Frank claimed that when he went back in, he found a note stating: “You will not find the cave or the body. I toke (sic) it with me.”

Without perusing the entire March 15, 1946 Tribune, the evidence suggests it was either a slow news day, or Col. McCormick didn’t have competent fact-checkers on the payroll. The next day the entire affair was revealed to be a hoax. Austin Police Captain Thomas Duffy took Frank aside and suggested he ‘fess up. The kid crumbled and said “I was only fooling, captain.”, and claimed he got the idea for the prank after seeing skeletons on display at the [Field] Natural History Museum the week before. The ventilated hat came to him after seeing “a moving picture murder mystery,” which just goes to show that movies and museums promote juvenile delinquency. Rather than booking him, the cops took Frank home. No foul play, no harm.

Frank’s next bout with fame wasn’t so amusing. On June 27, he was lighting fire crackers in a lot beside his house while his little sister Delores, 12, stood back and watched. Fireworks have long been illegal in Illinois—the first of many laws passed in 1941—prompting our more law-aborting citizens to drive to Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, Kentucky, and Missouri for their Fourth of July an New Year’s fix. Frank shopped locally, purchasing his firecrackers from an “big boy” up north in a Niles forest preserve. Unwisely setting them off in a metal Christmas tree stand, the pyrotechnics went without incident until Frank reached the grand finale. The final firecracker must have been huge, chock full of black powder, because the resulting blast cracked windows in three nearby buildings. The tree stand blew all to hell, flinging a chunk of steel 100 feet toward Delores, gouging her left side. She was taken to now-closed Walther Memorial Hospital and stitched up. While the Trib took the opportunity to address the issue of firework safety and legislation, nothing more was said about what happened to Frank and Delores. Yet another photo of Frank accompanies the article, the handsome lad holding shards of the shattered tree stand, looking a bit dazed.

In a turn, Frank’s last appearance in the paper was heroic, but tragic. On the evening of October 6—two days before the 75th anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire—flames broke out in his younger sisters’ room. Waking up to billows of smoke, little Rose, 6, and Shirley, 7, crawled out of their room and hid in another (one news source says the bathroom, another says it was the bedroom next door). Smoke continued to fill the building as Frank ran through the place, frantically searching for his sisters. He was soon joined by Chicago Fire Captain Frank J. Kubek, who saw the smoke pouring out on his way to work. The two Franks met and searched for the girls, but became separated. Kubek found his way out again and attempted re-entry from the rear door, but as he passed the side of the house he looked up to see the boy dangling from a window ledge, forced out by the flames. Telling Frank to let go, the captain caught him, severely injuring his back in the process.

During this time a neighbor, Henry Sandel (perhaps Sandei—the grittiness of the microfilm scan makes it difficult to determine), set off the fire alarm before heading into the flames to help. He was able to rescue mother Lillian and daughter Delores, guiding them out before rushing back in to help Kubek.

The two men thought they heard screams coming from the bathroom, and tried to kick in the door, but the fire forced them back, searing Sandel’s face, arms, and hands. Kubek found his way out, but Sandel had to exit a second-story window, smashing through the glass, grabbing hold of the tavern sign hanging outside, and dropping to the sidewalk without further damage. Horrifically, the sisters had suffocated by this point. Frank’s final Tribune photograph is a study in grief, he and his surviving sister Delores resting their heads against their mother’s sagging shoulders.

For us, perhaps charitably, that’s everything we know about young Frank T______, though there’s likely a family history somewhere that goes further. With hope he led a quieter life. A single family genealogy site reveals that he died in California in 1992. After a quick mental calculation, I realized that if he’d lived to the present day, Frank would be as old as my own father (living on the South Side the same time rank was living in Humboldt Park) today.

Built with the Hammer, Nails, and Assorted Other Tools of the Gods

It seems to me that Chicago’s historical Scandinavian population hasn’t received the notice and PBS documentaries due them. It’s a fine history, you know? One stretching back to the mid-1800s, when Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes established their presence on the Near North Side (aka: Swede Town), Douglas and Armour Square, North Lawndale, and near the intersection of Randolph and LaSalle (per the Encyclopedia of Chicago), and Clark St. According to one source, the latter was called Snusgatan, or Snuff Street (that’s snuff as in chewing/snorting tobacco), owing to the number of saloons in the area. I’m not sure of the veracity of that factoid, but it’s interesting nonetheless.

Eventually, Milwaukee Ave. became the main thoroughfare for a northwestward migration of Scandinavians. Similarities in language and culture encouraged them to stick together, though parts of town show, and still show, more prominent influence by one group or another. The Danes occupied the area surrounding North Ave., from Damen to Pulaski, for example, while Logan Square and Humboldt Park became Swedish and Norwegian enclaves. As evidence, note the 110-year-old statue of Leif Erikson guarding Humboldt Park, and the charmingly old world Minnekirken/Norwegian Lutheran Memorial Church—the only Norwegian language church left in Chicago—resting in Logan Square’s western elbow). Look closely in other north and northwest side neighborhoods as well and you’re bound to find evidence of immigrants from the land of ice and snow, and the midnight sun where the hot springs flow.

One little-noticed monument is located at 4146 N. Elston Ave. Built in 1922, the building is currently occupied by the Chicago Latvian Association. A recent bit of remodeling, however, tipped me off that it wasn’t always so. The entryway has long been topped by a sign for the community center, but a few weeks ago it was temporarily removed, in preparation for a new sign, revealing the original inscription.

Ivar Temple? IOV?

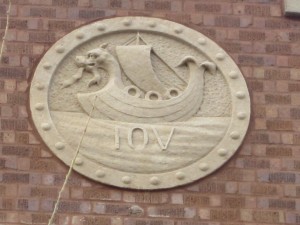

It’s interesting how a simple change can cause one to reassess an entire building. I’d suspected a Scandinavian background before, owing to the medallion near the top of the southeast wall. it features a Viking long-ship with a oversized dragon figurehead that looks like it might sink the ship prow-first. A little research revealed that IOV stands for the Independent Order of Vikings. Per Alex Axelrod’s book The International Encyclopedia of Secret Societies and Fraternal Orders, the IOV was founded in Chicago “as an ethnic fraternal insurance benefit association.” Between the 1880s and 1920s there were an awful lot of those—fraternal, quasi-masonic, and service organizations that promised health insurance while you were alive, and a decent burial and survivor care when you died. IOV membership was restricted to the community of Swedes, Swedish-Americans, and those married to either group.

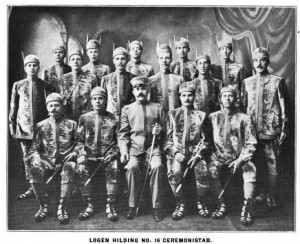

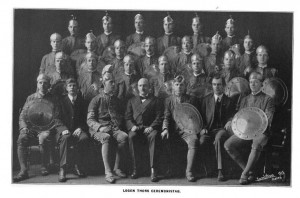

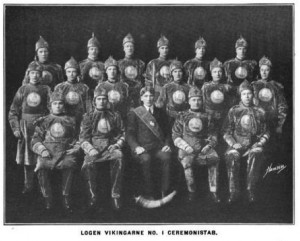

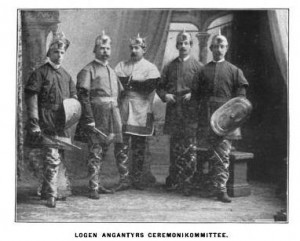

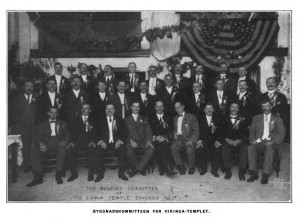

Eleven Swedish immigrant men established the organization on June 2, 1890, at 86 Sedgwick Street (no longer existent), in what was described in the club’s history as a “bachelor room.” Swelling with ethnic pride, and perhaps feeling a bit butch, they dubbed themselves the Vikingarne—Swedish for Vikings. By June of 1891, the organization was doing well, with more than 234 members. It cost $2 to join, with a quarter a month for dues. In return you earned $3 for sickness and $50 for funeral expenses.

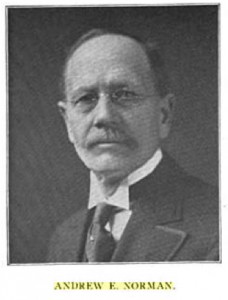

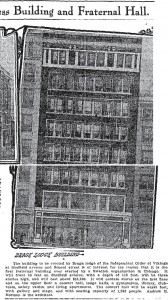

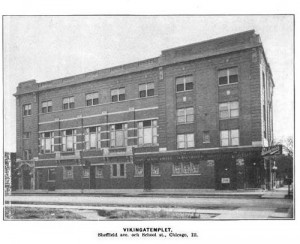

On December 12, 1891, the Vikingarne switched to their current name, the Independent Order of Vikings, possibly to compete with other, pricier fraternal orders cropping up at the time. Meetings took place around the city, usually in public halls, Odd Fellow and masonic temples, and the Phoenix Hall at Division and Sedgwick. Eventually they saved enough pennies to erect the North Side Viking Temple at the corner of School and Sheffield. Reportedly the first lodge building constructed by a Swedish organization in Chicago, its architect was (Swedish) gentleman named Andrew E. Norman. Norman was an interesting person, turning up in the Tribune as a craftsman, artist, architect, carpenter, contractor, and generally talented fellow. He also rocked the mustache/rimless spex look.

As for Irving Park’s Ivar Temple, as yet I have no information on who built it, or why the men of Ivar Lodge were flush enough to afford their own lodge hall. Funnily, information is plentiful, but it’s also in Swedish (see the history of the order, Runristningar: Independent Order of Vikings). According to the date on the building it was erected in 1922, and per a helpful e-mail from Mr. Ray Knutson of the Executive Committee for the Grand Lodge IOV, Ivar was “instituted” as Lodge #27 on Sept. 7 1906. Beyond that, little info exists—at least in English—though Mr. Knutson says he’ll let me know if he finds anything else.

It appears that the Latvian Community Center has been there since at least the 60s. Before and during that time, the temple hosted not only the Swedes of the IOV and the Independent Order of Svithiod (another fraternal order that brings Scandinavians from the US, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden under its aegis.) but also the American Legion and VFW. According to the Tribune’s social pages, it was a quite popular location for celebrating the golden wedding anniversaries of some rather doughy and dour looking old folks. Labor and socialism fans may be interested to hear that socialist Norman Thomas spoke at the temple on a tour through Chicago and Oak Park back in 1932.

And now, for lack of a more solid conclusion… VALKYRIES!