When not committing crimes against humanity, Hitler committed smaller ones against aesthetics. But while we owe him thanks for rendering toothbrush mustaches eternally unsavory, the man was a semiotic son of a bitch for taking the innocent swastika—a millennia-old symbol associated with power, energy, luck, divinity, and the life-giving sun—and turning it into a symbol of unfathomable evil. Argue all you want by citing which way the arms spin, Native American handicraft, and disconcerting/hilarious vintage photos, when most people see that crippled cross, their heads will fill with visions of jackboots and death camps. Naturally, that makes it all the more startling when the symbol turns up in our local architecture.

Until Hitler and his thugs reversed and dubbed it the Hakenkreuz (“hooked cross”) the swastika was a perfectly nice symbol. Historically and worldwide, it pops up in every culture. Deriving its name from the Sanskrit svastika—meaning “well-being” per Merriam-Webster—while modern folks immediately picture a cross with four branches bent at 90° angles, “turning” rightwards, the swastika comes in assorted shapes and sizes. You’ll find it in Buddhist and Hindu rites and temples; British heraldry; ancient Greek, Trojan, and Roman buildings and mosaics; native American arts and crafts (where it’s known as the “whirling log” among the Navajo); and, in its allegedly oldest incarnation, a 10,000 year old carving on a Ukrainian mammoth tusk. Sometime between the 1890s and 1920s, the symbol began to appear in company logos, clothing, medals, and elsewhere across North America. Architecture did not go unstamped.

There’s no hard and fast reason why the swastika became so popular back then. Contemporary archaeological digs may have had a hand in it, as 1890s and 1900s discoveries spurred revivals in decoration and forms. Explorations of the Pharaohs’ tombs in 1920s Egypt inspired Chicago’s Graceland and Rosehill Cemeteries’ obelisks, pyramids, and sphinx-attended mausoleums and tombs, and more eye-poppingly at the Reebie Storage Warehouse on North Clark Street. Swastikas were likewise carried over with the day’s humdrum obsession with neoclassicism/Italian renaissance revivalism. Rich folks requested their own (fingers crossed!) eternally standing Egyptian, Roman, and Greek edifices, so architects of the day carried over the conceits of the aforementioned styles. Others probably supported the symbol’s status as a good luck symbol—but why we don’t see horseshoes, four leaf clovers, and rabbit feet around town is unclear. Perhaps the swastika, like egg and dart patterns and dentils, was a simple yet striking way to decorate borders, friezes, and cornices. It may well be that people just thought the swastika looked awesome—though not in the way today’s racists do.

Tastes shifted. Sometime in the 20s, European nationalist groups adopted the symbol. Among these was the National Socialist Party, regrettably headed by a leader with art school background. Imagine the dismay of the world’s designers, companies, and architects, who’d placed swastikas every which way before Hitler came to power (though some showed feisty adherence to their brands). During the build-up to the war, materials with swastikas on them were often destroyed in shows of patriotism, while post-WWII the stigmatized swastika was obliterated or redesigned on many public and private buildings. Not everywhere. Cost, tradition, and a lack of angry protesters and the desire to deface public structures saved some swastikas—and it probably helped if they were the “good” left-rotating kind. Detroit’s Penobscot Building, for example, features a Native American tribute motif with legitimate, left-rotating swastikas.

In Chicago there aren’t many swastikas adorning public structures, but they’re there if you look for them. And you HAVE to look—usually up and out of the way.

Tessellating friezes are the most common way for the swastika to hide in plain sight in the Windy City. The proper term is the meander or Greek key design. Most often meanders appear in structures from the 10s and 20s, usually running the building’s perimeter a floor or three up amidst less memorable ornamentation. The middle building in the Gage Group (24 S. Michigan Ave.) features one, which most people probably miss while gazing at Louis Sullivan’s facade next door at 18 S. Michigan Ave. Evidence of Chicago architectural firm Holabird and Roche’s National Socialist sympathies? Not in the 1890s when they were built.

Columbia College’s Congress-Wabash Building (33 E. Congress Building), designed by Alfred S. Alschuler (who turns up later in this article), not only has a stylized swastika pattern but a set of terra-cotta Roman fasces for good measure.

Metropolitan Tower (formerly the Straus Building when constructed in 1924 by the firm Graham, Anderson, Probst & White) at 310 S. Michigan Ave. features another Greek key border, though these are broken up by squarish flower ornaments. The Tower is a swirl of symbology that would keep any conspiracy theorist awake at night. Aside from the swastikas, the building is capped by a pyramid topped by four bison statues holding a 20-foot glass ornament in the shape of a beehive on their backs. The “beehive, “symbolizing industry, is actually a multifaceted light fixture containing six 1,000 watt bulbs. Unless you have binoculars, none of this is viewable from the ground, but the beacon’s glow continues to burn blue each night.

Meanwhile, in an opposite corner of the Loop, the Builder’s Building (222 N. LaSalle) bears markings similar to the Metropolitan Tower’s. Not surprising, since they shared a firm in Graham, Anderson, Probst & White. Perhaps they bought in bulk.

Elsewhere, at Navy Pier, Bubba Gump shrimp-seeking tourists may double-take at the meandering swastikas decorating the towers of the Charles Sumner Frost designed building (1914). Only a few are visible, the rest of the frieze covered by a shield ornament.

Arguably, Greek key/meanders are swastika-inspired, perhaps, but not swastikas proper. Some meanders go without the distinctive broken cross shape (see the Marquette Building’s second floor for an alternate pattern).

Those seeking singular swastikas, however, must crane their necks to see them. The Baha’i House of Worship up in Wilmette is one place. It features swastikas (closer to fylfots than Hakenkreuz) toward the tops of its nine pillars, representing both Buddhism and Hinduism and sharing each pillar with a Christian cross, Hebrew Star of David, Muslim star and crescent, and the Baha’i nine pointed star.

Back downtown, the Bank of America Building’s (230 S. Clark St.) meanders periodically turn into left-spinning swastikas, with two set off at each corner. Once again, another 20s building (1924) built by Graham, Anderson, Probst & White.

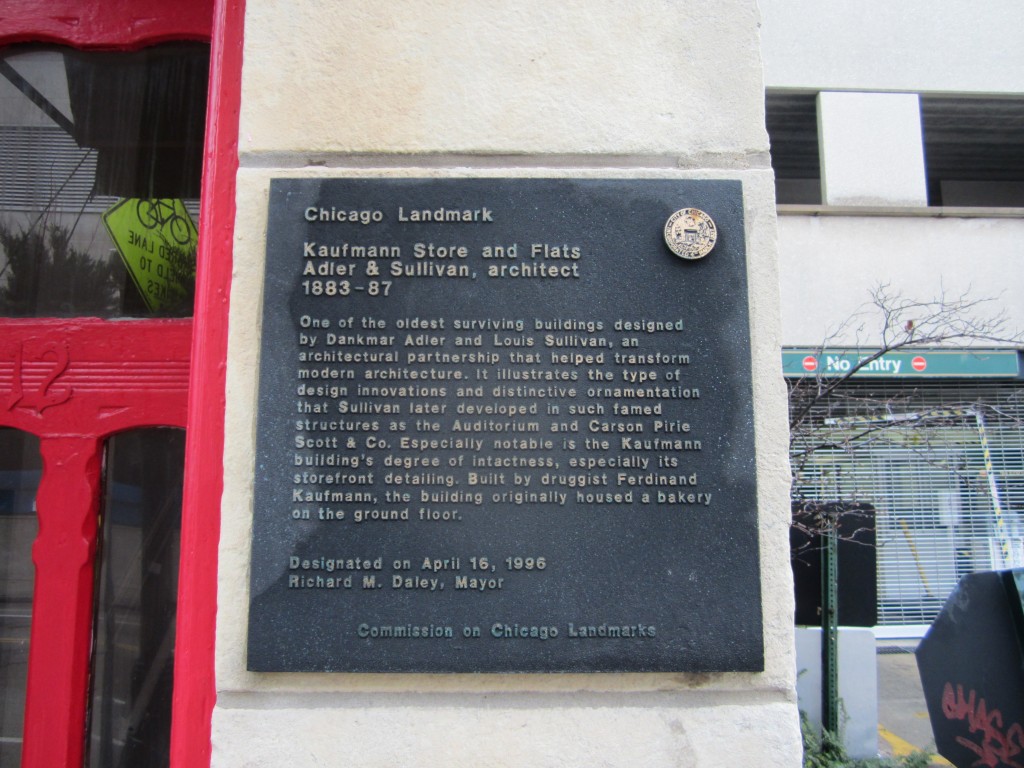

At the northeast edge of the Loop, we find an even more surprising swastika-decorated structure. Fans of Perfect Strangers—may God forgive you—will recognize Balki and Cousin Larry’s workplace the “Chicago Chronicle,” in Alfred S. Alschuler’s London Guarantee Building (360 N. Michigan Ave). Credit sequence footage and cutaway shots likely never showed the men gaping up with shock at the very distinct swastikas in the meander running across the building’s Wacker Drive and Michigan Avenue sides. At the time of writing, most of the swastikas are covered by trellises, but if you stand beneath them on the Wacker Drive side you can see a few. Alshuler, interestingly, was a student of Dankmar Adler’s, and also designed several Chicago synagogues (among other buildings), including the sanctuary for Hyde Park’s KAM Isaiah Israel synagogue.

If there’s a category for “lost” swastikas, Huehl and Schmidt’s 1912 Medinah Temple (600 N. Wabash Ave.) would head it. The Shriner clubhouse’s floors once featured good luck swastikas inlaid in the floor tiles before being carpeted over at some point. I recall visiting and seeing them in the late 80s. Photographic evidence has yet to turn up, but the swastikas have been noted elsewhere. I have no idea if Bloomingdale’s preserved them under the current flooring, and I doubt a phone call would garner further information.

Leaving downtown (and aside from the Baha’i House of Worship mentioned above) swastikas are scarce. Who’s to say how many were demolished, painted, or bricked over before and after the war? However, two surprising examples stand out in Logan Square. One house that likely continues to startle passers- and drivers-by is 2711 N. Kimball. A cheerful little red-bricked building with a charming peaked facade and not one but eight chipper little swastikas skipping above the lower cornice. The house was built in 1906, and while I’m no expert, owing to Logan Square’s formerly large Scandinavian population, I’d say it was designed by some jolly burgher to emulate architecture from the old country.

A similar house turns up a few blocks away on Central Park Ave. Built in 1916 or 1920 (sources vary), it’s basically the same design, though it lacks 2711 N. Kimball’s panache. The peaked facade is absent, the bricks a duller shade, and the swastika in the southeast corner is weirdly muddled. A failed attempt to eliminate the symbol’s stigma? Not the first, and probably not the last, attempt to do so in this town or elsewhere.