Mayfair Pumping Station, Part 3, Section 1, Fishing, Flooding, Falling, Choking, Stabbing

Presumably, the original conception drawing of the Mayfair Water Pumping Station.

Every raindrop promises life or death. Somewhere in-between rests inconvenience.

Here, lately, water is a petulant creature, severely perturbed by years of abuse. When it snows, it smothers us, and when it rains, it pelts, torrents, and creeps in, destroying basement furniture and carpeting like a bad houseguest. In the blasting heat of summer, our beaches threaten to become festering petri dishes of bowel-blasting bacteria. A city built on a swamp, despite Ellis S. Chesbrough’s best efforts to raise us from the muck, it feels like the water won’t leave Chicago alone. Constantly seeking its own level, it sometimes chooses to drag us down with it.

If things run smoothly, you won’t hear about it in the news. The bleeding leads, and the few times the Mayfair Pumping Station pops up in the Trib for the next seven decades usually involves violence, semi-biblical snafus, and moments where blood flowed like water and vice versa.

Jumping ahead to the 1960s, on January 5, the fire department arrived to douse a fire at the station. Ignited by welding equipment, a shower of sparks set ablaze a inconvenient pile of paper. While the station and its equipment weren’t damaged too badly, four firefighters were transported to Northwest and Swedish Covenant hospitals and treated for smoke inhalation. Two years later, in an exceedingly brief article, we learn that city worker William Dugan, 57, fell off a ladder July 10, while fixing the station’s roof. His fellow workers, reportedly, “were unable to explain the accident.” Mr. Dugan doesn’t turn up in the obituaries later on that week, so perhaps we can assume the best.

Then we have James and Nina Gardiner.

James, age 28, had, in a matter of speaking, been unfaithful. Not necessarily to his wife, Nina (23), but to water. If that sounds daft, that’s because it is, but allow me a momentary Fortean flight of fancy.

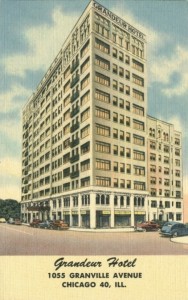

It was January 17, 1930, and Nina and James (two years married), were fighting—presumably again—in their rooms at the Grandeur Apartment Hotel (now Grandeur Apartments at 1055 E. Granville). James worked as an sanitary district engineer at the Mayfair Pumping Station; while Nina, to her great shame, was a secretary to Criminal Court Clerk John H. Passmore (seen here standing beside legendary conman Yellow Kid Weil). “To her shame,” because Nina was forced to take a job rather than keep a house, James having failed to bring home the bacon. James showed his, let’s call it “hydro-infidelity” by both avoiding work at the pumping station and running into the arms of the local saloons. According to the two available photos of her, Nina was a pretty young thing with devil-may-care eyes and a winning smile. James, perhaps unpossessed of a flapper’s allure, remains faceless to us.

Returning the the apartment—oh, let’s imagine it with a rusty sink, Murphy bed, and grim breakfast nook equipped with a hot plate and dingy side toaster—James had been absent for two days, returning without explanation and with hootch on his breath. Nina asked where the hell he’d been. James replied with his fists before turning in to bed.

Nina wasn’t having it. She opened a drawer, grabbed a revolver, carried it to where James lay, and began pistol-whipping the engineer. Unappreciative of her failure to ventilate his head, James slapped Nina around a little more then entered the bathroom—let’s picture it with a rustier sink and a single bulb dangling from the ceiling—to clean his wound. Washing the gore from his hair and face, dripping a far-too-late blood sacrifice into the sink, he told her more beatings were in the offing.

Nina replied with a butcher knife, stabbing upwards and slicing through his neck. The blade stuck out of his mouth like a metal tongue. Someone called the cops, and while James was taken to the Lake View Hospital, Nina was transported to the Summerdale police station at 1940 W. Foster. The Trib’s back page shows her cheerfully perched on a cop’s desk—Velma Kelly in furs—under photogenic interrogation by “Policeman William Garney.”

The Gardiners were absent from the papers for a few months. Until March 5, when the couple traveled down the Memphis-Bristol Highway on a reconciliation vacation. The facts are hazy about why the two kissed and made up, or even how far the case got in the courts. Maybe it was a different time, when a little light attempted homicide could be waved off by a romantic old fool of a judge. The couple barreled down Tennessee State Route 1 on a dark Wednesday night—then the rest of the tale played out like a Tom Waits song. The steering wheel broke, sending the car soaring over the embankment before planting it grill-first in a ditch. Buried deep in the mud, the water seeped in and reclaimed James and Nina. Shortly after, Mr. William A. Williamson of Mason, TN, saw the car’s taillights gleaming in the night and reported the accident. Nina and James were draped over the car doors, more than likely having tried to escape the car before the crash. And just like that, the engineer and stenographer were gone.

Sunk.

*******

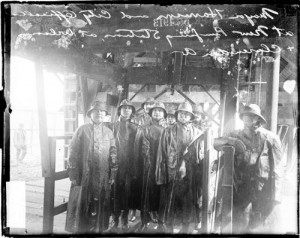

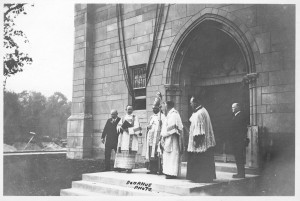

Bonus: Photos from the groundbreaking and opening of the Mayfair Water Pumping Station from the Chicago Daily news photographic archives.

Alderman Ellis Geiger digging at Mayfair Pumping Station while other officials watch.

[DN-0064323, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum]

Mayor Harrison and city officials standing in the Mayfair Water Pumping station

[DN-0064324, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum]

Joseph Kostner, Mayor Harrison and city officials, wearing rain coats and hats, standing on the street at the Mayfair Water Pumping Station

[DN-0064322, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum]