[I wrote this last year on my personal blog, but I thought it was worth, chuckle, resurrecting here.]

Last week’s house walk was a success. I worked at St. John’s Church as a docent and gofer Saturday morning and afternoon, switching between explaining the Christian symbology topping the lancets on the Advent Window, and setting up canopies, tables, and chairs for the beans and brats feast the church laid out for all visitors. I truly enjoyed myself—it’s rare that I have a live audience, and rarer still when they actually want to hear what I have to say.

After weeks (well, days) worth of study and practice, I was ready to show every interesting item between the narthex and sacristy. As it turned out, I was put in charge of showing off just the sanctuary and chancel—stage three of the tour as I explained to the house walkers.

Sorry, permit me to provide a quick glossary. The narthex is the entrance; the sacristy is the back-stage area where the priests and servers prepare for the service; the sanctuary is at the front of the church, while the chancel is the area surrounding the altar. At least that’s what I was told. I always heard the sanctuary comprised the interior of the church, and while I’d never encountered the word chancel before, I’d heard of the apse—the recessed area occupied by the altar, the tabernacle, the reredos, and other furnishings. (Didn’t understand a single word in the previous paragraph? I completely understand. For me it all comes from a Catholic boyhood and a little Wikipedia skimming. I won’t commit the sin of pride though—the sanctuary and chancel were more than enough, and I had the pleasure of describing three of the church’s prize possessions.

St. John’s is a small church. The congregation numbers at, I think, around 120 or so parishioners, and the building is the size of a large house. While not as sprawlingly awesome and ostentatious as the Catholic Holy Name Cathedral or St. James’, Chicago’s Episcopalian cathedral, St. John’s seems large even in its smallness. It reminds me of a nautilus shell, compact and curving into itself.

Just missing the Gothic Revival, but no doubt heavily influenced by it, St. John’s was erected in 1888. For chronological perspective, that’s the same year Arthur Conan Doyle dreamed up Sherlock Holmes and Jack the Ripper was murdering prostitutes in Whitechapel. Chicago’s Irving park—the northwest neighborhood St. John’s is situated in—was somewhat calmer back then. If memory serves, the area was originally called Grayland, because Sheriff John Gray (the first Republican sheriff elected in Chicago) owed much of the farmland there. Gray announced that the tract of land located at Byron and Kostner was available to anyone who promised to build a church. The Episcopalians—who were currently meeting in masonic halls and a room above a local pharmacy—took the challenge and constructed the current church.

Records state that the church was built by the Cookingham Co. My research turned up no such firm, though I did encounter another one named Cookingham and Clarke in a Trib article from 1886. Cookingham and Clarke announced that they were constructing “Chinese dwellings” (i.e., pagoda-inspired homes) in Ravenswood, another Chicago neighborhood. I haven’t looked into this yet, but I’m hoping that the “Chinese dwellings” were constructed and can be located (I doubt it).

Here’s where things get interesting, yet murky, so we must use a bit of conjecture. Cookingham of Cookingham and Clarke was a fellow named Peter. He had a brother named Theron who lived in Irving Park and worked as a contractor. The very helpful Mr. Tim Samuelson, Chicago’s redoubtable cultural historian, found a family photo of the Cookingham’s and posited (but admitted that this is not a certainty) that Theron very likely was the contractor, and Peter likely could have been St. John’s architect. My research turns up ads announcing applications for builder’s permits by a W.H Cookingham as well, leading me to think this was a family operation. Tim suggested the Britishness of their surname lends some credence to the Cookinghams being Episcopalians. Sounds like an excellent starting point for further research.

Here’s where things get interesting, yet murky, so we must use a bit of conjecture. Cookingham of Cookingham and Clarke was a fellow named Peter. He had a brother named Theron who lived in Irving Park and worked as a contractor. The very helpful Mr. Tim Samuelson, Chicago’s redoubtable cultural historian, found a family photo of the Cookingham’s and posited (but admitted that this is not a certainty) that Theron very likely was the contractor, and Peter likely could have been St. John’s architect. My research turns up ads announcing applications for builder’s permits by a W.H Cookingham as well, leading me to think this was a family operation. Tim suggested the Britishness of their surname lends some credence to the Cookinghams being Episcopalians. Sounds like an excellent starting point for further research.

On enters St. John’s through the narthex on the west side, passing through two red doors. According to tradition, the doors are painted red to symbolize entering the church under the protection of the blood of Christ. Sounds like it’s more of an Episcopalian tradition, and an image search for “red doors Episcopalian church” seems to bear this out. Ascending the stairs and entering the nave—the area containing the pews and aisle—the visitor can note two gothic revival elements.

1. Take a broad view of the scene and you’ll notice that the aisle is eventually bisected by a horizontal stretch of area between the pews and the sanctuary, forming a cross—not by accident.

2. The hammerbeam roof, composed of several large pieces of timber that take the weight and thrust of the roof and transfer it to the church’s stone walls. The problem is that St. John’s doesn’t have stone walls, and 20 years ago they noticed the walls were pulling away from the sides under the roof’s weight. A photograph from the archives shows the beams were about 2 1/4″ out of plumb. Not good. Tie rods and support bars were installed and painted well enough to blend in with the wood. I sure do like that hammerbeam roof—gives the place a mead hall feel. Christ the Viking.

Most of the stained glass windows at St. John’s were installed during the 60s and 70s and have pretty but bland Renaissance-inspired appearances. With the exception of the 1988 window, which takes full advantage of that era’s love of jagged abstraction. The sanctuary, however, features Irving Park’s oldest, intact stained glass window known as the Advent Window. The Advent Widow is the gift of the Children League of the Holy Child, a group formed before the church existed by a Mrs. Florance (the church’s Tennessee marble baptismal font is dedicated to her). After reading the Apostles Creed together every Saturday, Mrs. Florance and the children would sew squares to be sewn in turn into quilts and sold. From 1888 to 1924, the Advent Window occupied the west wall, while the church entrance was set in the northwest corner. In 1924 they dug a basement, and the church was shifted two feet northwards. The narthex was constructed, and the Advent Window was reset in the sanctuary’s northeast wall.

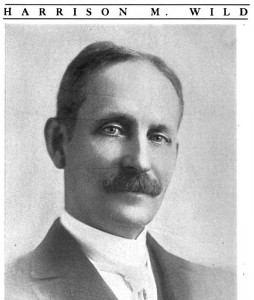

Directly across from the Advent Window you’ll find the church’s 110-year-old Kimball pipe organ. The W. W. Kimball Company was mostly known for piano manufacturing and sales, but from 1890 to 1942 they also built pipe organs. St. John’s organ was dedicated in 1900 by local organist/fin de siecle rock star Harrison Wild—a gentleman of great talent and tremendous mustache. The organ was once operated by a bellows, operated by wee boys who sat behind the organ and pumped it during the service. Later on a pipe was run into the church and the organ was water-powered before eventually being converted to electric. Wild wasn’t the only individual who tickled the ivories at St. John’s. Herbert E. Hyde, a child prodigy, played it from age 13 to 16. Hyde later went on to play for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and St. Luke’s Episcopal Church up in Evanston. Hyde spread out into the theater as well, writing music for children’s musicals and plays, including one written by Lord Dunsany, proto-scifi/fantasy writer and figure of great inspiration to H.P. Lovecraft.

The final object of pride is the reredos against the chancel’s rear wall. Installed in 1944, the reredos features four paintings by painter and parishioner Theon Betts. Mr. Betts came from an artistic family, and I mean that in the strictest sense since every one of them, from Daddy on down was a brush-slinger. Theon’s brother Louis was likely the star of the family, though not a household name (he did, however, render an impressive portrait of lumber magnate Martin Ryerson, currently residing at the Art Institute of Chicago). Theon was no slacker, however, and turned out four subdued, dreamy paintings of St. Francis, Mary, St. John, and St. Thomas Aquinas.

The tour passed through the sacristy, which once held a small chapel with a fancy, but now MIA, altar. The fun part came at the tour’s end in the back rooms. Once a much larger room, it was divided by drywall into several classrooms in the 1980s. Unfortunately, this covered up a sweeping ceiling and all traces of the former gymnasium—save for the very loud bell attached to the east wall, which once marked the rounds during the boxing matches they once held up there. OLD-FASHIONED EPISCOPALIAN BOXING MATCHES. Awesome.

The tour passed through the sacristy, which once held a small chapel with a fancy, but now MIA, altar. The fun part came at the tour’s end in the back rooms. Once a much larger room, it was divided by drywall into several classrooms in the 1980s. Unfortunately, this covered up a sweeping ceiling and all traces of the former gymnasium—save for the very loud bell attached to the east wall, which once marked the rounds during the boxing matches they once held up there. OLD-FASHIONED EPISCOPALIAN BOXING MATCHES. Awesome.

I don’t have any especially whacky house walk stories. The crowd was attentive and well-behaved. The only true eccentric was a guy in a trenchcoat, who first asked me if I was “the reverend” and then curiously advised me that our kitchen fire extinguishers weren’t of the correct grade (he recommended K grade extinguishers). My fellow guides, especially Angela, the church historian, were all lovely people. One of them, Olive, was good enough to snap a picture of me. Behold, Mr. Dan Kelly: DOCENT.

—Dan Kelly