Built with the Hammer, Nails, and Assorted Other Tools of the Gods

It seems to me that Chicago’s historical Scandinavian population hasn’t received the notice and PBS documentaries due them. It’s a fine history, you know? One stretching back to the mid-1800s, when Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes established their presence on the Near North Side (aka: Swede Town), Douglas and Armour Square, North Lawndale, and near the intersection of Randolph and LaSalle (per the Encyclopedia of Chicago), and Clark St. According to one source, the latter was called Snusgatan, or Snuff Street (that’s snuff as in chewing/snorting tobacco), owing to the number of saloons in the area. I’m not sure of the veracity of that factoid, but it’s interesting nonetheless.

Eventually, Milwaukee Ave. became the main thoroughfare for a northwestward migration of Scandinavians. Similarities in language and culture encouraged them to stick together, though parts of town show, and still show, more prominent influence by one group or another. The Danes occupied the area surrounding North Ave., from Damen to Pulaski, for example, while Logan Square and Humboldt Park became Swedish and Norwegian enclaves. As evidence, note the 110-year-old statue of Leif Erikson guarding Humboldt Park, and the charmingly old world Minnekirken/Norwegian Lutheran Memorial Church—the only Norwegian language church left in Chicago—resting in Logan Square’s western elbow). Look closely in other north and northwest side neighborhoods as well and you’re bound to find evidence of immigrants from the land of ice and snow, and the midnight sun where the hot springs flow.

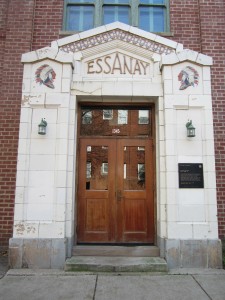

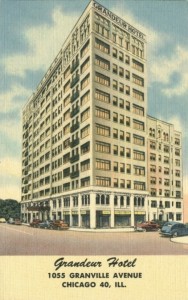

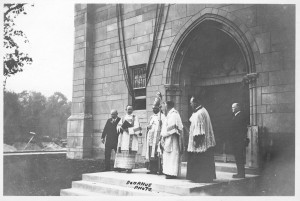

One little-noticed monument is located at 4146 N. Elston Ave. Built in 1922, the building is currently occupied by the Chicago Latvian Association. A recent bit of remodeling, however, tipped me off that it wasn’t always so. The entryway has long been topped by a sign for the community center, but a few weeks ago it was temporarily removed, in preparation for a new sign, revealing the original inscription.

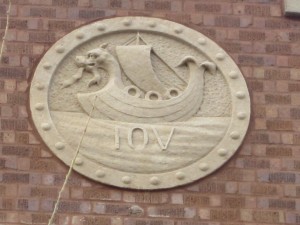

Ivar Temple? IOV?

It’s interesting how a simple change can cause one to reassess an entire building. I’d suspected a Scandinavian background before, owing to the medallion near the top of the southeast wall. it features a Viking long-ship with a oversized dragon figurehead that looks like it might sink the ship prow-first. A little research revealed that IOV stands for the Independent Order of Vikings. Per Alex Axelrod’s book The International Encyclopedia of Secret Societies and Fraternal Orders, the IOV was founded in Chicago “as an ethnic fraternal insurance benefit association.” Between the 1880s and 1920s there were an awful lot of those—fraternal, quasi-masonic, and service organizations that promised health insurance while you were alive, and a decent burial and survivor care when you died. IOV membership was restricted to the community of Swedes, Swedish-Americans, and those married to either group.

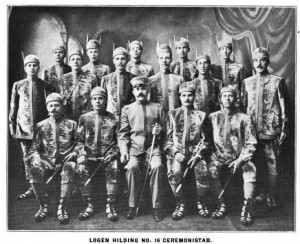

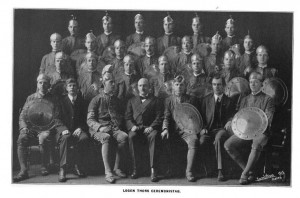

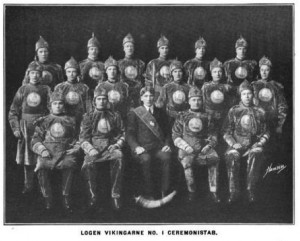

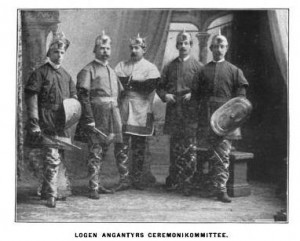

Eleven Swedish immigrant men established the organization on June 2, 1890, at 86 Sedgwick Street (no longer existent), in what was described in the club’s history as a “bachelor room.” Swelling with ethnic pride, and perhaps feeling a bit butch, they dubbed themselves the Vikingarne—Swedish for Vikings. By June of 1891, the organization was doing well, with more than 234 members. It cost $2 to join, with a quarter a month for dues. In return you earned $3 for sickness and $50 for funeral expenses.

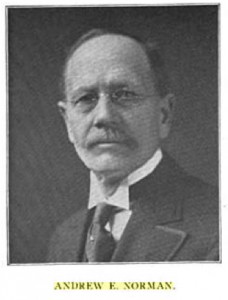

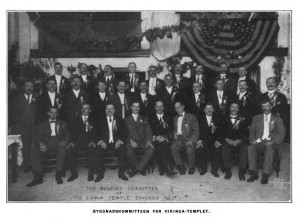

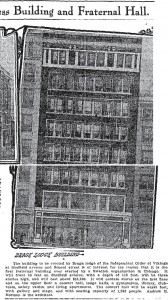

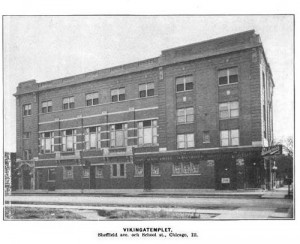

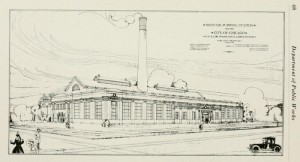

On December 12, 1891, the Vikingarne switched to their current name, the Independent Order of Vikings, possibly to compete with other, pricier fraternal orders cropping up at the time. Meetings took place around the city, usually in public halls, Odd Fellow and masonic temples, and the Phoenix Hall at Division and Sedgwick. Eventually they saved enough pennies to erect the North Side Viking Temple at the corner of School and Sheffield. Reportedly the first lodge building constructed by a Swedish organization in Chicago, its architect was (Swedish) gentleman named Andrew E. Norman. Norman was an interesting person, turning up in the Tribune as a craftsman, artist, architect, carpenter, contractor, and generally talented fellow. He also rocked the mustache/rimless spex look.

As for Irving Park’s Ivar Temple, as yet I have no information on who built it, or why the men of Ivar Lodge were flush enough to afford their own lodge hall. Funnily, information is plentiful, but it’s also in Swedish (see the history of the order, Runristningar: Independent Order of Vikings). According to the date on the building it was erected in 1922, and per a helpful e-mail from Mr. Ray Knutson of the Executive Committee for the Grand Lodge IOV, Ivar was “instituted” as Lodge #27 on Sept. 7 1906. Beyond that, little info exists—at least in English—though Mr. Knutson says he’ll let me know if he finds anything else.

It appears that the Latvian Community Center has been there since at least the 60s. Before and during that time, the temple hosted not only the Swedes of the IOV and the Independent Order of Svithiod (another fraternal order that brings Scandinavians from the US, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden under its aegis.) but also the American Legion and VFW. According to the Tribune’s social pages, it was a quite popular location for celebrating the golden wedding anniversaries of some rather doughy and dour looking old folks. Labor and socialism fans may be interested to hear that socialist Norman Thomas spoke at the temple on a tour through Chicago and Oak Park back in 1932.

And now, for lack of a more solid conclusion… VALKYRIES!