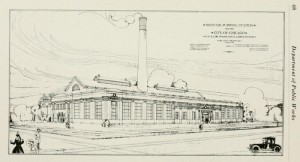

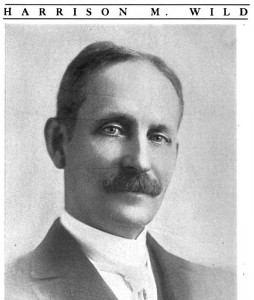

During his stint as Chicago’s city architect, Charles W. Kallal designed, or at least oversaw the construction of multiple municipal buildings across town. Mr. Kallal—identified as “City Architect” on a plaque near the pumping station’s front door—is a bit of a cipher. Finding his grave was easy; locating a photo of the man was near-impossible (Dominican University has one in their files; I’ll soon stop by to pick up a scan, so stay tuned). Born of Bohemian-American stock on July 8, 1873, Charles William was originally baptized Karel Vilem (at least per one genealogy site). I suspect he Americanized his name to ease assimilation. Little turns up about the man’s life until 1897 when he collaborated with architect Joseph Molitor on the former St. Vitus Church (1814 S. Paulina) in Pilsen. We know he married Miss Barbara Birnbaum at some point, and the two raised a flock of kids—five daughters and a son (the latter of whom went MIA in 1945 while serving in the southwest Pacific before being declared dead a year later).

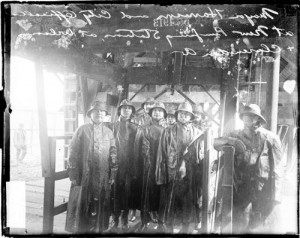

Professionally, Kallal became city architect during Mayor Fred Busse’s administration. It was a civil service gig, and he served under several mayors, including Carter Harrison, Jr., and William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson. Per the 1912 Chicago City Manual, Kallal and his department, the Bureau of Architecture oversaw:

“…the preparation of plans and specifications on which contracts are based for…construction, repair and alteration of all buildings other than schools and the City Hall, supervises the work of construction, etc. Architectural services are rendered to the Police, Fire and Health Departments, the Bureaus of Engineering and Streets and the House of Correction.”

What remains unclear is how much Kallal actually designed himself versus contracting outside architects. Were there enough hours in the day for one man to create a city?

Whether bureaucrat or Herculean city-builder, Kallal’s name frequently pops up in trade rags of the day—mostly periodicals with stultifying names like Electrical World, The Heating and Ventilating Magazine, The Metal Worker, and Water and Sewage Works—connecting his name with several existing, demolished, and perhaps never-erected buildings. Obviously, he kept busy, either drawing up and/or submitting plans for numerous Chicago police, fire, pumping, and power stations, bath houses, building additions, and, by one account, the city’s first outdoor natatorium (oddly referred to as an “artificial swimming hole,” what we would call a pool). While neither particularly ingenious or innovative, Kallal’s buildings have a wonderfully nostalgic air, recollecting the age of sleeve garters and handlebar mustaches. They are old-fashioned and unpretentious, possessing an amiable civility and admirable lack of cynicism.

******

The Bureau of Architecture didn’t just build fire stations, beach houses, and artificial swimming holes, however. Per the 1913 Chicago City Manual, Kallal was charged by Commissioner of Public Works Lawrence E. McGann, with a prestige project: restoring the Chicago Water Tower, which had, in the previous 42 years, gone to seed. Mayor Harrison lived nearby, and had long wanted to see the tower and its accompanying pump house brought up to snuff. The City Manual reports that Kallal and his workers repaired the structure’s ground facings and replaced much of the broken glass. The Manual also provides amazing descriptions of how much work Kallal and his men had cut out for them. The Chicago Fire’s most famous survivor did not resemble the shiny castellated phallus standing at Chicago and Michigan Avenues today:

“The lighter stones and stone ornaments of the tower were torn off and hurled a distance by the superheated wild air; the heavier white stones were blackened and stained; the foundations were involved and so weakened that the tower leaned, giving to Chicago for a time the second marvel of the kind in this world of marvels.”

While he didn’t build it, Kallal served as custodian of Chicago’s City Hall, a Classic Revival Structure designed by Holabird and Roche in 1911. Kallal kept things tidy, overseeing the chief janitor, the building’s chief operating engineer, and the entire maintenance staff, including, interestingly, all of City Hall’s carpenters and cabinet-makers. Non-Chicagoans may recognize it as the building where the Bluesmobile finally broke down.

*****

In December 1913, Kallal and Health Commissioner George B. Young visited the eastern US on a fact-finding mission. Hardly a glamorous junket, the two toured contagious disease hospitals in Cincinnati; Washington, DC; and unspecified other cities to generate ideas for a similar hospital in Chicago. In a Trib interview, Young did all the talking, stating that the the two men had “gathered valuable suggestions” and promising they would “plan a hospital which will be pretty nearly ideal when we finish our investigation.”

This was no doubt the same “hospital with glass rooms” promised in an article in the 1913 issue of Heating and Ventilating Magazine. Kallal’s plans for the new $300,000 “isolation hospital” promised creepy “…glass hospital rooms, equipped with telephones, permitting persons recovering from contagious diseases [Writer’s note: mostly tuberculosis] to be visited by relatives and friends.” The hospital would be located at 31st Street and Marshall Boulevard—land currently occupied by Cook County Jail–but ended up instead at 3026 S. California Blvd as the Municipal Contagious Diseases Hospital. As of April 25, 1915, Kallal’s office was at work on the plans, but Young raised Cain about the location. The City Council Committee wanted it built near the old hospital in Lawndale. Young nixed that, saying it was a waste of money and good buildings.

On January 4, 1914, Kallal got a raise, along with Health Commissioner Young and Deputy Building Commissioner Robert Knight. Building Commissioner Henry Ericsson (who shares several commemorative plaques with Kallal) did not. Not to worry—Ericsson felt little pain, already making $6,000 and requesting $10,000. Kallal, however, got a $1,000 bump to $5,500, while Knight went from $4,000 to $5,000. All this took place during Mayor Carter Harrison, Jr.’s stint as mayor from 1911 to 1915.

By 1915 the administration changed, and the impressively corrupt (even among Chicago mayors) Mayor “Big Bill” Thompson was in charge. Moreover, April 28, 1915, the Trib reported that Charles’ hospital had a flaw. The first ward buildings of the new hospital had settled by 14 inches. Reported the Trib:

“It is said caissons would have been provided and that insufficient borings were made.”

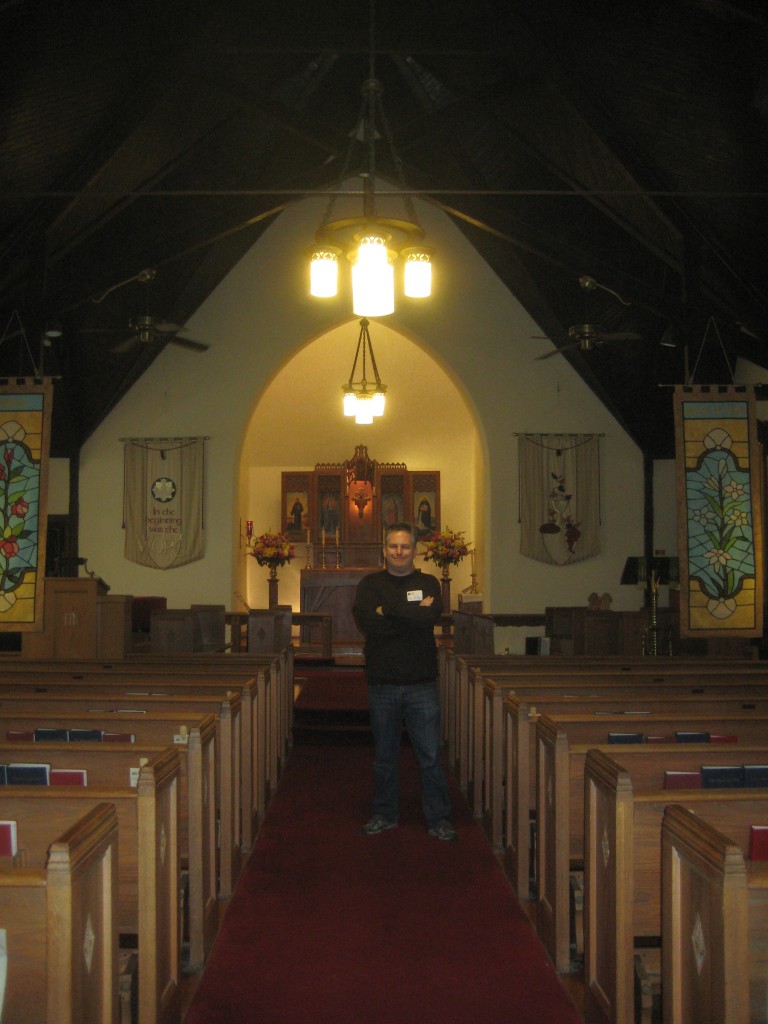

Costs to fix the problem were calculated at $37,000, and rumors flew that Kallal might get the pink slip. It appears he didn’t, however—or at least there was no follow-up story. Kallal’s obituary shows he was affiliated in some way with the firm of Cram and Ferguson, historically, builders of college and religious buildings. The very nice folks at Cram and Ferguson told me they have no records of Kallal’s years with the firm, but I’d hazard to guess that he worked for them in the 1890s (as suggested by his work with Joseph Molitor) rather than moving on to them after his stint as city architect.

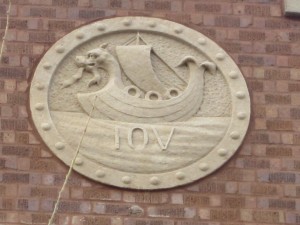

Besides the Mayfair Pumping Station, Kallal’s most readily recognized structure is likely Chicago Firehouse #78 (1052 West Waveland). Standing in the shadow of Wrigley Field, it was built in 1915. The book A Chicago Firehouse states that even though Kallal’s name appears on the plaque out front, he probably didn’t draw up the plans for the fire station himself. Regardless, Mayfair Pumping Station, the firehouse, and the Department of Gas & Electricity Southwest Substation (mentioned below) reveal elements suggesting a shared hand. The brickwork is set to form alternating patterns, culminating in checks, pinwheels, and other shapes. The ornamental shields, medallions, and, in the case of the pumping station, the stylized beastie (possibly a lion, possibly a dragon, perhaps a sea serpent) over the front door, bespeak a common source for ornamentation. But that’s just a personal observation.

Mayfair Pumping Station

Mayfair Pumping Station

Chicago Firehouse #78

Chicago Firehouse #78

Kallal was also integral to the creation of a sizable, snazzy bath house at 4501 N. Clarendon Avenue in 1916, at the immensely popular Clarendon Avenue Beach (see these sites for views of the building and Turn of the Century Chicagoans frolicking in the surf and sandy turf). Later expansion of Lincoln Park’s beachfront cut into Clarendon’s, and the area became the traditional park it is today. Regrettably, the bath house was deprived of its towers and tile roof during a 1972 renovation, and converted into a community center, giving no indication of its former glory.

Much further south, all the way down in Washington Heights, we find a kid brother to the Mayfair Pumping Station in the Department of Gas & Electricity Southwest Substation (10227 S. Halsted). The familiarly checked brick building shows that even though you’re municipal and utilitarian, that doesn’t mean you can’t be cute. I haven’t trekked down to the substation yet, but Flickr photographer/bicyclist Eliezer Appleton graciously gave permission to link to his snapshots of the place.

*****

A quiet man, archivally speaking, Kallal left behind few words (though Dominican University in River Forest, IL, holds several letters from Kallal dating from the time he acted as Rosary College’s architectural advisor—he was, apparently, a devout Catholic. Evidence suggests he only published one article on architecture, “The Standard Handball Court,” which appeared in Architecture and Architect Magazine and discusses the construction of such courts for fire stations (Googlebooks provides limited access to this journal; I’d be much appreciative if anyone out there with a copy could send me a scan). In the Tribune, I turned up a single quote in the Dec 31,1918 article “Ask City $35,000 Rental for Old Herald Building.” Addressing the council finance committee by letter regarding the purchase and use of the old, OLD Daily Herald building as a police station, Kallal left behind the immortal words, “the minimum requirements for operation [of the Herald Building were] $35,362, exclusive of heat.” He co-wrote the letter though, so we can’t even be sure those were his words.

Sadly, Kallal never made it out of middle age. He died March 7, 1926, at the age of 52 from an ear infection, and currently rests in St. Adalbert’s Cemetery in Niles, IL. Interestingly, his family’s plot rests beside the crypt of George “Papa Bear” Halas, long-time coach and owner of the Chicago Bears.

While he may not have been an aesthete and philosopher like Louis Sullivan or Frank Lloyd Wright, or a sculptor of cities like Daniel Burnham, Charles W. Kallal did design useful buildings not unpossessed of charm. They may not be symphonies in stone, but they’re certainly catchy little ditties in brick and glass.

Later note: At the suggestion of Mr. Appleton, I checked the Chicago Landmarks site for other buildings connected with Mr. Kallal. Two more fire stations are located at 2179 N. Stave St. and 330 W. 104th St., while the Lincoln Public Bath House hides at 1019 N. Wolcott Ave. I might take a Father’s Day journey around town to collect photos of every Kallal I can find.

—Dan Kelly

Previous

Next, Floods, Fish, and Other Mayhem at, Around, and Connected with Mayfair Pumping Station